Workaholism: Conceptualization, Assessment, Prevalence, Consequences, and Treatment

- by Ε. Πανουσόπουλος

-

Εμφανίσεις: 4138

Abstract

Based on existing literature, a brief presentation of the conceptualizations and empirical assessment of the phenomenon of workaholism is attempted. More emphasis is given in the view of workaholism as a pathological - under certain circumstances – behavior, more akin to that of an addictive behavior. Accordingly, studies are reviewed examining the prevalence, and consequences of such an addictive behavior. Moreover, a review of suggested preventive interventions and treatment modalities of workaholism is presented alongside with recommendations and suggested implications for such therapeutic endeavors based in the relevant literature. Finally, the need for more research is highlighted in order for a more sound documentation of the defining features, constituents, antecedents, and primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions of workaholism to be succeeded.

Workaholism: Conceptualization, Assessment, Prevalence, Consequences, and Treatment

During the last forty years and since the first conceptualization of workaholism as a behavioral addiction owing compulsive features as well as aversive consequences there has been a relevant increase in the number of studies examining theoretical and empirical links of the topic (Andreassen, 2014; Quinones & Griffiths, 2015). Oates (1971) was the first to address the addictive nature of workaholism as a chronic lifestyle pattern that shares cognitive and behavioral similarities with a substance-based addiction, that of alcoholism, and defining it as the “the compulsion or the uncontrollable need to work incessantly” (Oates, 1971, p. 11) of a person “whose need for work has become so excessive that it creates noticeable disturbance or interference with his bodily health, personal happiness, and interpersonal relationships” (Oates, 1971, p. 4).

Since then the concept of workaholism has been viewed by a variety of approaches further depicting the multi-faced dimensionality of the issue as well as a theoretical confusion regarding the conceptualization and etiology of workaholism (Andreaseen 2014; Taris, Schaufeli, & Shimazu, 2010; Quinones & Griffiths, 2015). Quantitative approaches have conceptualized workaholism as referring to excessive working hours, generally working more than it is required (Machlowitz, 1980), or working excessively up to point that other areas of life are neglected (Persaud, 2004). Some approaches view workaholism form a trait perspective suggesting that workaholics may hold perfectionistic, compulsive traits such orderliness, obstinacy, and rigidity, as well as a higher need for achievement (Mudrack, 2004; Porter, 1996), while others conceptualize workaholism as a coping mechanism in order to avoid painful internal emotions stemming from unhappy personal and emotional lives (Robinson, 2000) or as a compensatory maladaptive lifestyle to poor psychological integration and to a lack of connectedness and intimacy with other people (Berglas, 2004). Finally, there are approaches that view workaholism as a complex process stemming from an interplay of cognitive (e.g. obsessional thinking about work), behavioral (working excessively and being rewarded for doing so), and affective (deriving gratification mostly from the act of working and not from the content of the work itself) components (Ng, Sorensen, & Feldman, 2007).

Workaholism: A Disorder or A Valued Lifestyle?

Apart from the aforementioned diversity in the approaches of the concept of workaholism, it appears that a controversy also exists as to whether workaholism is a pathological addictive condition or just a behavior that fits well within the context of the contemporary Western way of life (Ng et al., 2007). For example it has been suggested that people who are characterized as workaholics are those who just consciously select to work hard in order primarily to derive gains from excessive work both in terms of material (e.g. income, lifestyle) as well as of psychological gains such as recognition, self-worth, meaning, and responsibility (Machlowitz, 1980). Furthermore it has been theorized that certain types of workaholics can be considered as assets for organizations and society in general as such persons can be suggested to manifest a strong motivation towards work and productivity. For example, Scott, Moore, and Miceli (1997) suggest that workaholics can be distinguished into three types, compulsive-dependent, perfectionists, and achievement-oriented, with the latter type to come closer to a more valued ideal type for modern Western societies. In the same line, Spence and Robbins (1992) identify three core features of workaholism: (a) work involvement, including work commitment and devotion, (b) an inner drive that generates inner pressures to work, and (c) work enjoyment. Based on the relevant prevalence of each of these three dimensions they further distinguish among enthusiastic workaholics, non-enthusiastic workaholics, and work-enthusiasts. All three types are theorized to be high on work commitment and devotion, with the types characterized as workaholics to manifest a high drive for work in the form of an inner pressure to constantly work or think about work that resembles compulsion. Furthermore, they suggest that the difference between enthusiastic and non-enthusiastic workaholics, and thus between adaptive and pathological workaholism respectively, lays to the degree of enjoyment they derive from their work, with non-enthusiastic workaholics to depict a lack of work enjoyment and accordingly to display a more maladaptive excessive working behavior. Finally, beyond the theoretical debate as to whether and to what extent workaholism is a disorder or just an excessive behavior, it appears that even if it is excessive, however it is not associated with a substance, is not related to criminal behavior, and what’s more, is a behavior that is mostly considered as a virtue for modern industrialized societies (Andreassen, 2014). As such it appears that workaholism as a behavioral pattern is one of the most rewarded, at least in the world of business organizations, while it has also strong links with the defining materialism and consumerism features of the western industrialized culture that favors the acquisition of wealth and goods as the prototype of a successful living (Berglas, 2004; Csiksentmihayli, 1999; Holland, 2008; Kashdan & Breen, 2007).

With respect to the aforementioned controversy regarding the nature and the defining features of workaholism the following can be noted. First, in terms of the behavioral manifestation of excessive work, a differentiation between work engagement and workaholism as a maladaptive condition could prove to be more effective in defining core features of pathological workaholism (Taris et al., 2010). In line with the differentiation between workaholics (enthusiastic or not) and work-enthusiasts (Spence & Robbins, 1992), it has been additionally proposed that the distinctive feature of workaholism from high work engagement is the intensity of the inner drive that in the case of workaholics takes the form of a compulsion similar to that of any addictive behavior, it stems mainly from extrinsic motivational forces and it is associated with little or no gratification from the content of the work per se (Taris et al., 2010). A second point regarding the degree to which workaholism can be viewed as a pathological condition is associated with the temporal and situational context where the behavior takes place (Griffiths, 2005). As such, in order for excessive work to be viewed as a maladaptive and pathological dependency it must have a temporal consistency and time length beyond specific short time periods when a person may manifest overwork. Also, a person’s interpersonal environment can be viewed as another contextual factor that may put a different perspective on workaholism. For example as suggested by Griffiths (2005), excessive work exhibited by a young adult single man that is not linked with interpersonal conflict may not be viewed as workaholism, whereas the same behavior enacted by a middle-aged adult with an expanded interpersonal environment (e.g. spouse, children, social contacts) can lead to interpersonal conflicts and to a diminishing social life further suggesting the problematic nature of the behavior. Moreover, consideration must be taken into account regarding the general macroeconomic environment that is prevalent in a specific society where individual working behavior takes place.

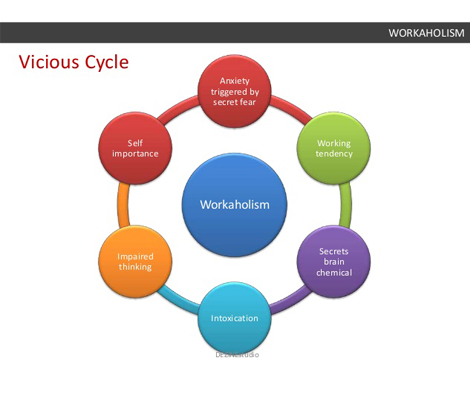

A final point regarding the nature and the characterization of excessive working can be drawn from the degree of resemblance that excessive working behavior may manifest with that of an addictive behavior. Sussman, Lisha, and Griffiths (2011) suggest the following features that can characterize a behavior to be a process addiction: (a) the behavior is associated with pleasure, arousal, and generally appetitive effects, (b) the behavior is manifested with preoccupation, is manifested repeatedly, and absorbs a great time from the person, (c) the behavior is enacted with a diminished sense of control and volition (d) the behavior is associated with negative consequences in the person’s other areas of life, and (e) there is gradually a heightened need for engagement in the behavior (tolerance), while cessation or abstinence from the behavior is linked with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Accordingly, for an excessive working behavior to be characterized as a “process addiction” and to be labeled as pathological workaholism the aforementioned features must be embedded in the manifestation of the behavior. As such, a person’s engagement with his/her work must (a) elicit pleasure and appetitive effects, (b) diminish the person’s social and interpersonal life via excessive engagement with work, (c) manifest a loss of control of time working, (d) associated with negative outcomes (e.g. conflicts with other life domains and with interpersonal and social relationships, feelings of burned out), and (e) encompass subjective reports of distress when not working, in order to be viewed as work addiction (Sussman, 2012). In the same line, Griffiths (2005) suggests six components as essential features for an excessive work behavior to be characterized as workaholism reflecting a process addiction: (a) salience, when work dominates a person’s cognitions (e.g. constant preoccupation with one’s work), affect (e.g. cravings for work), and behavior (e.g. poor socializing and interpersonal behavior); (b) mood modification, referring to the workaholics subjective experience of a “high” and euphoric feelings, or conversely of a tranquilizing “numbing” or “escape” feelings when engaged in work; (c) increased tolerance equated with gradually over time increasing working hours; (d) withdrawal symptoms experienced when not working (e.g. anxiety, depression); (e) conflict, either interpersonal or conflicts with other activities (e.g. hobbies, other interests, social life) that are perceived as antagonists to the workaholics main behavioral preoccupation with work; (f) relapse, manifested as the re-emergence of excessive working behaviors after unsuccessful attempts to gain control over compulsive overworking.

Assessment, Prevalence, and Consequences of Workaholism

Based on the above conceptualizations of workaholism as a process addiction, as well as a generally pathological condition with aversive consequences, specific self-report instruments have been constructed in order to assess the degree to which an excessive working behavior can be characterized as workaholism. These instruments refer to the Workaholism Battery (WorkBat; Spence & Robbins, 1992), the Work Addiction Risk Test (WART; Robinson, 1999), the Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS; Schaufeli, Shimazu, & Taris, 2009), the Non-Adaptive Personality Workaholism Scales (SNAP-WORK; Clark, McEwen, Collard, & Hickok, 1993), and the Bergen Work Adiction Scale (BWAS; Andreassen, Griffiths, Hetland, & Pallesen, 2012). These scales tap upon components and features of workaholism as a process addiction (e.g. BWAS), while others give emphasis to specific aspects of the construct as consisting of both excessive and compulsive behavioral components (e.g. DUWAS), as well as linked with specific personality traits (e.g. SNAP-WORK scale). Although they appear to have limitations regarding their internal consistency, to present low convergent validity among them, and to depict variations in terms of the way they perceive the phenomenon of workaholism (Andreassen, 2014; Quinones & Griffiths, 2015), nevertheless they have obtained some empirical validation, and generally they represent an attempt to operationalize the construct and to provide screening tools for assessing excessive working behavior and accordingly inform primary and secondary interventions aimed at minimizing the consequences of workaholism as a maladaptive process addictive behavior.

Based also on the aforementioned measures some studies have managed to estimate prevalence rates of workaholism. Reported rates however appear to vary considerably depending on the conceptualization of workaholism and on the scales utilized for assessment. As such in a study of general Canadian population prevalence rates as high as 18 percent have been reported (Sussman, 2012). High prevalence rates have been reported also by other studies ranging from 23 (Aziz & Zickar, 2006) to 30 percent (Andreassen et al., 2012) of the general working population, while in a meta-analytic study of behavioral addictions a prevalence rate of about 10 percent of the general U.S. population has been estimated (Sussman et al., 2011) to exhibit workaholic behavior. Moreover, workaholism appears to be more prevalent among working people who hold managerial and leadership positions (Andreassen, Hetland, Molde, & Pallesen, 2011), while within specific business sectors, such as agriculture, construction, consultancy, and commercial trade it appears that manifestations of workaholism are more prominent (Andreassen et al., 2012; Taris, van Beek, & Schaufeli, 2012). Finally, with respect to comorbidity with other addictions it has been suggested that a 20 percent of workaholics also exhibited other substance and behavioral addictions (Sussman et al., 2011), such as caffeine, nicotine, sex, and internet addictions (Quinones & Griffiths, 2015).

Regardless of the differences and variations in the perspectives of workaholism and its estimated prevalence rates, what may be more significant in the attempt to delineate the nature of excessive working as a pathological dependence are the negative consequences associated with workaholism. As such excessive working behavior having the features of excessive and compulsive, out of control, work commitment alongside with a subjectively experienced difficulty disengaging from work or feelings frustrated when prevented from working is associated with a variety of negative outcomes in a person’s life domains such as health, social and interpersonal life, work performance and satisfaction, and overall levels of well-being. More specifically, workaholics appear to experience more health problems particularly when elevated stress is experienced at work (stress related physiological symptoms, fatigue, sleep problems) and to depict more burnout symptoms. Also, workaholism is associated with increased work-family conflicts as manifested in elevated levels of marital estrangement, poorer family problem solving and communicative capacities in terms of workaholic-spouse relationship, while with respect to workaholic-children relationships these appear to be more strained with negative consequences for the children. Finally, workaholics seem to exhibit poorer social life functioning in contexts outside of work, to report lower levels of psychological and subjective well-being with less experience of positive emotions and lower levels of life satisfaction, while in most of the cases workaholism is inversely related with work efficiency and performance (for a review see Andreassen, 2014; Giannini & Scabia, 2014; Sussman, 2012).

Prevention and Treatment of Workaholism

Interventions aimed at reducing workaholism can be clustered into preventive interventions and interventions linked with the treatment of workaholism per se. Preventive interventions can be conceptualized to occur in societal and organizational levels, while treatment of workaholism can occur both in organizational level, but mainly at an individual level (Sussman, 2012).

Prevention

With respect to preventive interventions, from a societal level, a change of cultural values placed on a more balanced relationship between work and personal life could prove to be effective in preventing the adoption of specific lifestyles that are linked with the acquisition of power, control, and materialistic goods and subsequently extrinsically motivated excessive work. In the same line public policies that bestow work closings during national or established holidays while in parallel promote mass media campaigns that foster the importance of recreational activities or a “work smarter and not harder” attitude in favor of increasing society’s members psychological well-being could facilitate a more balanced relationship to work (Sussman, 2012). However, such policies may not always be affordable or be part of a public policy’s agenda, as other factors (e.g. macroeconomic and microeconomic environment, fiscal priorities, well-established cultural rules in favor of excessive working, etc.) may hinder the adoption of such policies. Moreover, little research has been devoted to the examination for possible positive effects of the implementation of such measures while accordingly the need for theoretical and empirical studies regarding the interrelationships among public policies, work engagement, and individual well-being is highlighted in order for a sound documentation of such policies to be succeeded (Sussman, 2012).

From the level of organizations, two points can be suggested to work as motivational forces for organizations to adopt a preventive attitude towards the phenomenon of workaholism. First, business organizations usually seek and hire employees who are highly motivated and are willing to exhibit commitment and high work engagement. Second, as noted earlier regarding the consequences of workaholism, workaholics although manifest high work engagement with excessive hours of working, nevertheless they appear to exhibit lower work efficiency and performance. These two points can highlight the need for organizations to be in a position to detect and differentiate workaholism from work engagement, and accordingly to implement interventions that can prevent it. As in the case of interventions at the societal level, employees and business organizations can adopt norms and cultures that both foster work engagement and work efficiency as opposed to workaholic behaviors, and accordingly reinforce a more balanced view of work-personal life equilibrium. The following interventions are suggested to be adopted by employers in order for minimizing phenomena of workaholism and for creating business organizations within which employees can partially find satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs (Deci & Ryan, 2000) of autonomy, competence, and relatedness that in turn foster a sense of elevated psychological well-being: (a) establishment and maintenance of a balanced equilibrium between effort and reward based on efficiency and not on overworking, (b) provision of stimulating and optimally challenging job tasks according to each employee’s capacity, (c) provision of continuous and constructive feedback (Andreassen, 2014; Hetland, Hetland, Andreassen, Pallesen, & Notelaers, 2011). Moreover, the role of management leaders is highlighted as top level managers can serve as role models for other employees by communicating their values, attitudes, priorities, and personal biases regarding work engagement and work performance (Kovjanic, Schuh, Jonas, Quaquebeke, & Dick, 2012). To that end the concept of transformational leadership referring to the role of higher level managers as inspirational motivators who exhibit individual consideration and provide intellectual stimulation for their co-workers can been seen as a managerial attitude that can foster efficiency, productivity, and employee satisfaction, avoiding rewards of manifestations of excessive and compulsive work engagement with doubtful efficiency (Hetland & Sandal, 2003; Kovjanic et al., 2012)

Treatment

Treatment for workaholism can occur at the organizational level, mainly at the form of secondary interventions once the problem of workaholism has been detected among employees, as well as a tertiary form of intervention at the individual level of the workaholic once the problem has been a well-established stance of the individual. At the organizational level, the adoption of work-life balance programs that may provide employees with psychoeducation training, such as time management, setting boundaries, stress and relaxation techniques can depict primary and secondary forms of intervention for workaholism, while to this end the development and utilization of career counseling for employees can serve to the same direction (Andreassen, 2014).

At the individual level, specific psychotherapeutic modalities can be implemented for the treatment of workaholism. Self-help groups, cognitive behavioral (CBT) and rational emotive behavioral therapy (REBT), motivational interviewing, positive psychology interventions, and mindfulness-based psychotherapeutic interventions can be potential means of treatment. In the following paragraphs a brief account of these types of treatment interventions is attempted.

Self-Help Groups. Similar to the approach of the 12 steps programs adopted by anonymous alcoholics (AA), Workaholics Anonymous (WA) groups, originating since 1983 when they first appeared in United States, take the form of fellowships with frequent and regular meetings. Currently such groups exist worldwide, provide on and off line meetings, internet and helpline supports (Andreassen, 2014). As with AA, WA groups view workaholism as a disease which cannot be completely cured. During the meetings each member is prompted to tell his or her story to the other members, a process called “sharing”, while such sharings take an interchangeable form among members. To the workaholic such self-help groups can provide understanding, emotional support, universality, instillation of hope, as well as a social network in order to cope with feelings of isolation.

CBT & REBT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is based on the premise that it is the irrational maladaptive cognitions that create and perpetuate a problematic condition and maintain psychological distress. As such in the case of workaholism, it is suggested that what underlies work addiction are specific cognitive distortions, irrational beliefs and assumptions associated with unrealistic and unrelenting standards, “musts” and “shoulds”, worry scripts, and schemas that perpetuate a behavioral addiction to work. In the context of CBT, Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT) uses the ABC model to conceptualize a behavior, where A stands for antecedents or triggering stimulus of a behavior, B for a person’s beliefs, and C for consequences of the behavior. The aim of REBT approach is to define the irrational beliefs that mediate between the activating triggers and emotional and behavioral consequences of a workaholic’s behavior. Common patterns of beliefs or cognitive distortions for workaholics refer to demandingness (musts and shoulds), low frustration tolerance (e.g. perfectionism, unrealistic standards), and all-or-nothing thinking (Berglas, 2004). Once such beliefs/assumptions have been identified the next step for therapist and client is an attempt to challenge and replace them with more rational ones. To this end other techniques embedded in CBT can be utilized, such as cost-benefit analysis of workaholic’s behavior and beliefs, imagery, examination of worry-scripts scenarios, role-playing, and other techniques aiming at helping workaholics coping with unpleasant feelings, frustrations, and irrational beliefs (Burwell & Chen, 2002; Chen, 2006). Moreover, psychoeducation for time-management, stress and relaxation techniques can be added.

With respect to the effectiveness of REBT to the treatment of workaholism it appears that there is documentation for specific irrational beliefs to be linked with workaholism and such cognitions to be target for intervention that can reduce work addiction (Van Wijhe, Peeters, & Schaufeli, 2011), while both CBT and REBT appear to have promising results (Chen, 2006). However, at this point it must be noted that most individual cases of work addiction are rarely presented with workaholism as the presenting problem per se due to the social acceptability and rewards that follow such behavior (Burwell & Chen, 2002) thus making the direct implementation of REBT or CBT techniques more challenging or less relevant to possible workaholics’ presenting problems. In order for such therapeutic approaches to be effective, it is essential the formation of a strong alliance between therapist and workaholic client or among therapist, client and client’s family members that could highlight and make more apt for therapy the significance of the adverse consequences of workaholic behavior for the individual as well as for family members (Berglas, 2004).

Motivational Interviewing. Motivational interviewing can be another treatment approach for process addictions and in particular for work addiction (Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). This approach is based upon counseling principles (empathy, avoidance of confrontation and argumentation, client’s efficacy support) and communication skills (open questions, reflections of thoughts and feelings, affirmations and summarizations) while it entails specific therapeutic strategies for problem exploration, acknowledgment of client’s ambivalence for change, exploration of change motivation, collaborative setting of problems and goals for change. The focus of therapy is to bring forward workaholic’s thoughts and emotions embedded in excessive work behaviors in an attempt to foster self-discover of the negative aspects of workaholic’s addictive behavior and to cultivate intrinsic motivation for behavioral change. Confrontation and use of argumentation against the addictive working behavior is not suggested as such interventions may reinforce client’s resistance for change. Instead, change talk is encouraged with statements that encompass client’s reasons, needs, desires, and ability to change, based on the rational that the client will be able to hear himself or herself in propositions about current problematic conditions (e.g. “I should do something before my health breaks down”), wishes about the future (e.g. “I wish to spend more time with my children”), and how wishful states can be approached in order for client to start contemplating about change.

Positive Psychology Interventions. Burwell and Chen (2008) suggest positive psychology interventions and techniques in an attempt to reduce work addictive behavior. Based on a positive psychology perspective (Seligman, 2002; Seligman, & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) these interventions attempt to direct the focus from the negative aspects of the workaholic behavior (e.g. maladaptive cognitions, aversive interpersonal and social life consequences) to client’s positive aspects in order to emphasize workaholics’ strengths, positive human qualities, and generally to re-direct the focus to positive emotions, flow engagement, and to meaning-enhancing aspects of life. Specific techniques are used to facilitate client’s identification of personal strengths and to enhance their implementation in client’s everyday life activities in an attempt to refocus client’s attention, memory, and expectations to more positive aspects of life and generally to foster human qualities such gratitude and connectedness. Alongside, behavioral techniques focusing on self-caring practices, such as exercise, healthy diet, and spending quality time, can also be implemented for the development of a valued and guiding life vision.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Shonin, Gordon, and Griffiths (2014a) also suggest the implementation of mindfulness-based interventions to the treatment of workaholism as a process addiction, and especially as relapse prevention interventions. Although empirically there is little support for the use of mindfulness as an effective treatment for work addiction (limited to one case study of a single-participant; Shonin, Gordon, & Griffiths, 2014b), on the other hand there is evidence for the effectiveness of such interventions for substance addictions as well as for behavioral addictions such as gambling (Shonin et al., 2014a). The key treatment mechanism is suggested to be a perceptual shift in a person’s mode of responding to present moment sensory, cognitive, and affective experiences, the acknowledgment that such experiences are transient, and generally a focus of concentration to an active, full, and direct awareness of present moment experiences. The adoption of such a mindful approach is suggested to aid the individual in utilizing more adaptive coping styles in response to withdrawal symptoms, to subjectively felted dysphoric mood states, and to the compulsive and out of control work engagement, while in parallel can facilitate a person’s amplification of his or her life perspectives, the cultivation of self-compassion and self-respect, and to a re-evaluation of life priorities (Shonin et al., 2014a).

Implications for Treatment

Regardless of the therapeutic approach towards workaholism, it must be noted that preventing and treating workaholism is not an easy task as pathological work addiction is presented with features that can pose challenges to its prevention and treatment. In terms of society and organizations, as noted earlier there is a pragmatic cultural element especially in Western societies that appears to foster work engagement as a mean for accumulating materialistic gains which in turn appear to provide the basis for the acquisition of self-esteem and identity conforming to dominant lifestyles despite the heavy burden that such styles may place upon a person’s psychological and subjective well-being (Berglas, 2004; Burke & Cooper, 2008; Holland, 2008). The globalization of economy also heavily contributes to the spread of a consuming and materialistic life style exerting influence on one’s subjective sense of self, while even in Eastern societies collectivistic cultural norms place heavy importance to high work devotion and engagement as means for group acceptance and self-validation (Holland, 2008; Snir & Harpaz, 2009). Accordingly, at the individual level, prevention and treatment of workaholism can be hindered by the fact that workaholic behavior is mainly a socially acceptable one, is not stigmatized as other substance and process addictions (e.g. drug abuse, gambling, alcoholism etc.; McMillan, O’ Driscoll, Marsh, & Brady, 2001; Robinson, 2001), while complete abstinence cannot be a viable suggestion. Moreover, workaholics appear to be in denial of the problematic nature of their behavior (Robinson, 2001). Such individuals are more likely to seek treatment after being forced to do so by pressures from colleagues or family members due to the negative consequences of their behavior, or to be referred for counseling by medical services since it is more possible for workaholics to report health-related problems associated with their maladaptive working customs.

In addition, and with respect to individual therapeutic endeavors, caution is suggested to therapist’s stance towards the workaholic client. Berglas (2004) suggests the following points to be taken into consideration when dealing with workaholics: First, asking directly from a workaholic to withdraw from his/her working life or to downsize its subjective importance can constitute a serious reason for the workaholic client to terminate abruptly the treatment. Also, regardless of the preferred therapeutic modality it is advocated that a parallel focus on the psychological mechanisms that underlie the behavioral manifestations of pathological excessive working (e.g. self-esteem issues, issues related with client’s sense of self-identity and self-representation, interpersonal issues, possible narcissistic traits) can prevent future relapses while it may lead to sustainable client’s changes. Moreover, it is suggested for a therapist to adopt a flexible stance (e.g. in suggesting and setting treatment goals, in the employment of novel therapeutic techniques, in extending the therapeutic boundaries by involving client’s significant others, etc.) instead of adhering strictly to manualized protocols (as for example in the case of CBT/REBT), and to place great focus on achieving and maintaining a sound therapeutic alliance. Finally, in line with therapist’s suggested flexibility, it is also recommended that a more holistic-integrative therapeutic approach can be more effective in preventing and treating workaholism, in the sense that a mixture according to client’s individual needs embracing behavioral (e.g. relaxation, time-management) and quality of life interventions, forms of therapy varying among group, individual, and family therapeutic modalities, as well as addressing existential and spiritual issues alongside other more traditional approaches can prove to be more valuable towards fostering a life balance (Holland, 2008).

Conclusions

Although workaholism appears to be a well-embedded concept as well as a lay word utilized in developed and developing societies, however a lack of consensus still exists in scientific fields with respect to its definition, operationalization, and to its unique features. In the last years an increase in the studies examining the concept of workaholism has been documented, while currently an initial convergence in the constituents of workaholism appears to exist mainly in terms of its excessive and compulsive elements as well as of its negative consequences that place the concept of workaholism more akin to be conceptualized within a behavioral addictions model (Andreassen, 2014; Quinones & Griffiths, 2015; Sussman, 2012). Clearly more research is needed for the delineation of the concept and of the degree of the pathological dimension of workaholism. Cultural norms, economic pressures, and modern lifestyle issues on the other hand make this effort even more complex in terms of the multidimensionality of the concept (Holland, 2008).

Prevention and treatment of workaholism can occur at the societal, organizational, as well as individual level. Perhaps what currently makes more obvious the necessity for interventions at the business organizational level is the demand for work efficacy and performance succeeded within shorter temporal limits. At the individual level, tertiary psychotherapeutic interventions although can take many and various forms, from traditional manualized treatments to more holistic-integrative psychotherapeutic modalities, nevertheless more research is needed examining the effectiveness and efficacy of such therapeutic endeavors (Andreassen, 2014; Quinones & Griffiths, 2015; Sussman, 2012).

References

Andreassen, C. S. (2014). Workaholism: An overview and current status of the research. Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 3(1), 1-11. doi:10.1556/JBA.2.2013.017

Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Hetland, J., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a work addiction scale. Scandinavian Journal Of Psychology, 53(3), 265-272. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00947.x

Andreassen, C. S., Hetland, J., Molde, H., & Pallesen, S. (2011). 'Workaholism' and potential outcomes in well-being and health in a cross-occupational sample. Stress & Health: Journal Of The International Society For The Investigation Of Stress, 27(3), e209-e214. doi:10.1002/smi.1366

Aziz, S., & Zickar, M. J. (2006). A cluster analysis investigation of workaholism as a syndrome. Journal Of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 52-62. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.52

Burwell, R., & Chen, C. P. (2002). Applying REBT to workaholic clients. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 15(3), 219-228. doi:10.1080/09515070210143507

Burwell, R. & Chen, C. P. (2008). Positive psychology for work-life balance: A new approach in treating workaholism. In R. J. Burke & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The long work hours culture. Causes, consequences and choices (pp. 295–313). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Burke, R., J. & Cooper, B., C. (2008). The Long Work Hours Culture: Causes, Consequences, and Choices. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd, Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley, UK

Berglas, S. (2004). Treating Workaholism. In R. H. Coombs, R. H. Coombs (Eds.) , Handbook of addictive disorders: A practical guide to diagnosis and treatment (pp. 383-402). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Chen, C. P. (2006). Improving work-life balance: REBT for workaholic treatment. In R. J. Burke, R. J. Burke (Eds.) , Research companion to working time and work addiction (pp. 310-329). Northampton, MA, US: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Clark, L. A., McEwen, J. L., Collard, L. M., & Hickok, L. G. (1993). Symptoms and traits of personality disorder: Two new methods for their assessment. Psychological Assessment, 5(1), 81-91. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.1.81

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). If we are so rich, why aren't we happy?. American Psychologist, 54(10), 821-827. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.821

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The 'what' and 'why' of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Giannini, M., & Scabia, A. (2014). Workaholism: An Addiction or a Quality to be Appreciated?. J Addict Res Ther 5: 187. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000187

Griffiths, M. (2005). Workaholism is still a useful construct. Addiction Research & Theory, 13(2), 97-100. doi:10.1080/16066350500057290

Hetland, H., Hetland, J., Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S. & Notelaers, G. (2011). Leadership and fulfillment of the three basic psychological needs at work. Career Development International, 16, 507–523.

Hetland, H. & Sandal, G. M. (2003). Transformational leadership in Norway: Outcomes and personality correlates. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12, 147–170.

Holland, D. W. (2008). Work addiction: Costs and solutions for individuals, relationships and organizations. Journal Of Workplace Behavioral Health, 22(4), 1-15. doi:10.1080/15555240802156934

Kashdan, T. B., & Breen, W. E. (2007). Materialism and diminished well-being: Experiential avoidance as a mediating mechanism. Journal Of Social And Clinical Psychology, 26(5), 521-539. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.5.521

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Quaquebeke, N. V., & Dick, R. (2012). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees' needs as mediating links How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of.. Journal Of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1031-1052. doi:10.1002/job.1771

Lundahl, B. W., Kunz, C., Brownell, C., Tollefson, D., & Burke, B. L. (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research On Social Work Practice, 20(2), 137-160. doi:10.1177/1049731509347850

Machlowitz, M. (1980). Workaholics: Living with them, working with them. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

McMillan, L. W., O'Driscoll, M. P., Marsh, N. V., & Brady, E. C. (2001). Understanding workaholism: Data synthesis, theoretical critique, and future design strategies. International Journal Of Stress Management, 8(2), 69-91. doi:10.1023/A:1009573129142

Mudrack, P. E. (2004). Job involvement, obsessive-compulsive personality traits, and workaholic behavioral tendencies. Journal Of Organizational Change Management, 17(5), 490-508. doi:10.1108/09534810410554506

Ng, T. H., Sorensen, K. L., & Feldman, D. C. (2007). Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: a conceptual integration and extension. Journal Of Organizational Behavior, 28(1), 111-136.

Oates, W. (1971). Confessions of a workaholic: The facts about work addiction. New York, NY: World.

Persuad, R. (2004). Are you dependent on your work? BMJ Careers, 329, 36–37.

Porter, G. (1996). Organizational impact of workaholism: Suggestions for researching the negative outcomes of excessive work. Journal Of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 70-84. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.70

Quinones, C., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Addiction to Work: A Critical Review of the Workaholism Construct and Recommendations for Assessment. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 53(10), 48-59.

Robinson, B. E. (1999). The Work Addiction Risk Test: Development of a tentative measure of workaholism. Perceptual And Motor Skills, 88(1), 199-210. doi:10.2466/PMS.88.1.199-210

Robinson, B. E. (2000). Workaholism: Bridging the gap between workplace, sociocultural, and family research. Journal Of Employment Counseling, 37(1), 31-47.

Robinson, B. E. (2001). Workaholism and Family Functioning: A Profile of Familial Relationships, Psychological Outcomes, and Research Considerations. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 23(1), 123-135.

Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., & Taris, T. W. (2009). Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in the Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal Of Comparative Social Science, 43(4), 320-348. doi:10.1177/1069397109337239

Scott, K. S., Moore, K. S., & Miceli, M. P. (1997). An exploration of the meaning and consequences of workaholism. Human Relations, 50(3), 287-314. doi:10.1023/A:1016986307298

Seligman, M. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY, US: Free Press.

Seligman, M. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Shonin, E., Gordon, W. V., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014a). Mindfulness as a Treatment for Behavioural Addiction. J Addict Res Ther 5: e122. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000e122

Shonin, E., Gordon, W. V., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014b). The Treatment of Workaholism With Meditation Awareness Training: A Case Study. Explore, 10(3), 193-195. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2014.02.004

Snir, R., & Harpaz, I. (2009). Cross-cultural differences concerning heavy work investment. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal Of Comparative Social Science, 43(4), 309-319. doi:10.1177/1069397109336988

Spence, J. T., & Robbins, A. S. (1992). Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. Journal Of Personality Assessment, 58(1), 160-178. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5801_15

Sussman, S. (2012). Workaholism: A review. Journal of Addiction Research and Theory, Suppl. 6, 4120. doi:10.4172/2155-6105. S6–001

Sussman, S., Lisha, N., & Griffiths, M. (2011). Prevalence of the addictions: A problem of the majority or the minority?. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 34(1), 3-56. doi:10.1177/0163278710380124

Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Shimazu, A. (2010). The push and pull of work: The differences between workaholism and work engagement. In A. B. Bakker, A. B. Bakker (Eds.) , Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 39-53). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press.

Taris, T. W., van Beek, I., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Demographic and occupational correlates of workaholism. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 547-554. doi:10.2466/03.09.17.PR0.110.2.547-554

Van Wijhe, C. I., Peeters, M. W., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). To stop or not to stop, that’s the question: About persistence and mood of workaholics and work engaged employees. International Journal Of Behavioral Medicine, 18(4), 361-372. doi:10.1007/s12529-011-9143-z